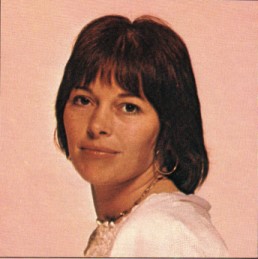

Interview with Lesley Duncan

August 1987

by Ian Chapman

Special thanks to Ian Chapman for letting us post this interview and to David V. Barrett for facilitating.

Whilst some will know her for the songs she's written and others for the inordinate number of background sessions she participated in over the years, most will remember Lesley from the singer/songwriter era of '69 - '73, when she was at her most prominent. Back then, hardly a day went by without a track from her ‘Sing Children Sing’ and ‘Earth Mother’ albums being played on the radio. Elton John, a friend from her session days, included one of her numbers, ‘Love Song’, on his ‘Tumbleweed Connection’ album and at one point, they were calling her ‘the English Carole King’.

But only a few years later, following two more albums and further singles for GM, Lesley went into a somewhat self-imposed lull - or as she puts it, “I dropped out and went to live in Cornwall”, re-emerging only occasionally; in 1979, with the aforementioned charity single; and most recently in 1982, with a single for Korova.

Lesley’s entry in the NME Book Of Rock briefly encapsulates her 70s period. Yet very little or nothing has ever been documented about her very early career, or the string of singles she cut for Parlophone, Mercury and RCA in the 60s. Now living happily in Oxfordshire with her second husband, musician Tony Cox (ex of the Young Idea), Lesley is happy to talk about those early days, and to fill in a few of the gaps in her story…….

One can't help but wonder how a girl born in Stockton-On-Tees came to gain entry to the music business down in London. Was there a musical family tradition perhaps?

"Not professionally, no, but we had a piano in the house, and my mother was a good pianist - she played in clubs - and my grandfather sang in the chapel choir too, so there was always music around the house. I got involved in the business through my brother Jimmy (who later went on to manage the Pretty Things). He'd always had a burning ambition to be a songwriter. I'd been travelling around the country doing various things - waitressing in Scarborough, mother's help in Wimbledon - and I was in London in 1963 working as a waitress, when he turned up with a handful of songs one day and said, 'Right, I'm really going to do it now, I'm going to be a songwriter'. And I said, 'Well, anybody can do that!', so he said, 'Well, why don't you come with me then?'

So I banged together a couple of country and western songs in my head - I had no instruments, I was living in a bed-sit in Notting Hill Gate at the time - and we both walked into a publisher's, Francis, Day & Hunter, and just sang our songs, completely unaccompanied. Two days later, we went back and they gave us both a contract for a year! Jimmy got slightly more than me, he got £10 a week, and I got £7 a week, guaranteed for a year. So on Friday I was a waitress, and on Monday I was in show business. It was all bluff really, I was just bluffing!"

So how did the transition from writer to recording artist come about?

"Well, I'd never sung anywhere, not in pubs or anything; but I was making demos of my songs, and I had this manager who took one of them to Parlophone. They gave me a recording contract just on the strength of the demo - I didn't even audition, which was quite unusual in those days. The manager turned out to be a bit of a crook, actually - I still have very acrimonious letters from him to my mother, 'cos I was a minor then, saying that he would let me out of my contract with him if I paid him £10 he said I owed him! It's very funny, those days are like another incarnation now!"

The demo that became Lesley's first single was ‘I Want A Steady Guy’, a waltz-like ditty slightly after the fashion of Cliff's ‘Bachelor Boy’. It was backed with a song not written by Lesley, ‘Movin' Away’, which was recorded originally by another Lesley, American singer Lesley Gore. That first record was credited to Lesley Duncan & the Jokers. And the Jokers were…?

"Carter and Lewis, Viv Prince on drums, who later joined the Pretty Things, and Les Reed on piano - all struggling musicians at the time."

There were two Parlophone singles. The second, ‘You Kissed Me Boy’ from early '64, was what they used to call a 'beat ballad'. Its hollow, ringing style suggested a vague nod in the Phil Spector direction. Was he an influence with that record?

"I suppose so, slightly ... I was very excited by the kind of sound he was making, but bear in mind that we only had four-track recording then, so we just played loudly! The producer of those first two records was Ron Richards, who used to work with George Martin at EMI."

What about other, more general influences?

"When I first started writing, I didn't have any pop influences at all, apart from the usual - Elvis, Bill Haley, Little Richard and all the rock and roll stuff. Although, because I grew up in the late 40s and early 50s, it was quite late on for me when rock and roll happened, so probably the main influences I had would be what we now call standards - Peggy Lee, Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan, which is why I've always tended to be more 'ballady' than anything. I used to be glued to the radio all the time then, so I kind of grew up with the standards. Mind you, there was one later influence, or rather somebody that I very much admired, and that was Jackie De Shannon. In fact, we met, and it was very strange - we discovered that we were both Leos, and that we had so many things in common - it was a very strange sensation. But I used to love her material, and I'd go into Dick James' all the time and say 'Have you got anything new from Jackie De Shannon?'"

Both sides of the second Parlophone single gave writing credits to Lesley and Jimmy Duncan. Did the two of them collaborate often, I wondered?

"No, we never collaborated! I wrote those! No, hang on, there was one, a Beryl Marsden record that we both wrote together, ‘Love Is Going To Happen To Me’, that was the only one we ever genuinely collaborated on. We just had a kind of writing partnership. I don't know why…it was funny days…it was a bit like the Lennon & McCartney thing, I suppose. Mind you, there were never any credits for me on any of my brother's songs!!"

Shortly afterwards came a move to the Mercury label. Why such a short stay at EMI?

"I think the reason I left Parlophone was that I got very cheesed off because I took a song to the producer - it was the Doris Troy number, ‘Just One Look’ - and said, 'This is a really great song, I'd really like to record this, I'm sure it's gonna be a big hit'. And he said, 'No, no, I can't see that being a hit, can't see it…’ And then a few weeks later he did it with the Hollies!! He recorded it with them, which really cheesed me off. And there were a couple of other songs too that went a similar way, so I left. Not that I was a very dedicated careerist at that time - I never have been, not ever, ever - I was just having a good time, just having fun, and if I found a song I thought might be nice to sing, I just went and took it."

The first Mercury single surfaced in 1964, the self-penned "When My Baby Cries", an ornate ballad that has dated very little.

"Yes, very pretty song that, isn't it. I listened to that a few months ago and I thought it was so pretty - I mean, you don't always like stuff at the time."

I mention the cover version that Tony Hatch cut in '65 with a young Czech singer, Yvonne Prenosilova, which comes as a surprise to Lesley, although mention of another version by the Poor Souls on Decca seems to ring a bell. She tells me that Dusty Springfield always said she wanted to record it too, but never got round to it, and we both agree that it would have suited her down to the ground.

The next outing was ‘Just For The Boy’, an excellent cover of an American original by the Essex, and a song suggested to Lesley by her A & R man. The flip was another Duncan original, the delightful ‘See That Guy’. A happy-go-lucky little floater, it had more than a hint of Motown bounce. When I cite it as a particular personal favourite, she gives a slightly wry laugh that suggests that she herself wasn't too happy with the way it turned out. She elaborates when I ask whether she did in fact listen to much Motown back then.

"No, I never even had a record-player. You see, I used to live in crummy bed-sits, and I'd sit in cafes and compose these things in my head, without an instrument. Then I'd have to get together with an arranger and he would laboriously sit at the piano while I'd say, 'No, not that chord, that one' - and by a process of elimination we'd figure out what chords I had in my head. With ‘See That Guy’, it would be the arranger that gave it that slightly Motown feel, not me, because it was done very much like that in those days. You'd sing your song to the arranger, he'd come in with his arrangement of how he saw the song, do the session and that would be it."

Doubly frustrating, one imagines, when the singer also happened to be the song's author. But if the arranger had so much influence, then what was the role of the producer?

"Interesting one, that. They were far less active in those days, and far less involved."

More of an executive presence perhaps – which may explain why British records from this period, unlike American ones, rarely bear the name of the producer, whereas the Musical Director is nearly always credited. And how much influence did the singers wield?

"They didn't have much final say in how it was done, either. I remember Dusty being very rebellious in that way, she had very strong ideas. On the record that followed ‘See That Guy’ though, I did in fact start to get more involved myself artistically, saying 'Look, this is not how I want it', and getting cross, you know, and I think it shows on the record. I was still stuck with the same old arrangers, but there was a slightly moodier feel to it, d'you think?"

Indeed. ‘Run To Love', the record in question, was issued in October '65 and both that song and its flip, ‘Only The Lonely & Me’, pre-empt precisely the melodic ballad style that would later become Lesley’s trademark in the 70s.

But the one that Lesley still cites as her own favourite was the final Mercury 45, a criminally-neglected ballad entitled ‘Hey Boy’. Another self-composition, it radiated class and rivaled anything that the Goffin & Kings and Bacharach & Davids were doing Stateside at the time.

"Yes, ‘Hey Boy’ was very much the way I wanted it and I especially like that one best. And Dusty sang on that, of course, along with Madeline Bell."

Further excellence lay on the flip, with a hauntingly simple rendition of Ray Davies’ ‘I Go To Sleep’:

"I just fell in love with that. I thought it was a really lovely song."

I offer my own opinion that it is perhaps the best version ever committed to wax and she considers the compliment levelly:

"Well…I thought it was better than whoever did it recently…the Pretenders. Yeah, I thought it was very pretty."

And that five-star single marked the end of Lesley’s stay with Mercury. As an avid admirer of this particular stage of her career, I couldn’t help but ask if there might still be anything unreleased?

"I think there were a few bits and pieces ... I remember doing ‘Yesterday’ when it was just in the publisher's, which I thought was a very beautiful song - that's unreleased. But not a lot was, because you tended to take in your one or two songs, routine them, and do them."

We then turned to the subject of vocal backgrounds. Lesley became almost as well known for her session work as for being an artist in her own right. Dusty Springfield fans will already be aware of Lesley's background contributions to practically all of her post-'64 Philips material - and even those were but a fraction of the many sessions Lesley has been involved in over the years. So how did this particular offshoot of her career come about?

"There was Madeline Bell, Kiki Dee, Dusty and myself, all on the same Philips group of labels and we all got very cheesed off because we couldn't get the sound we wanted from any of the backing choirs that were available at the time. There were the Breakaways, the Ladybirds or the Mike Sammes Singers then. The Breakaways were slightly harsh and nasal in the beginning, though they got better, much better, later on. The Ladybirds, who again improved later on, were a bit square….and the Mike Sammes Singers were absolutely ‘choral society’! So Madeline, Kiki, Dusty and I found that if we got together and pooled our resources, we could make a sound that we liked better. And so we all started singing on each other’s records. I was on lots of Dusty's, loads - ‘Some Of Your Lovin’’, that's still on of my favourites. It’d probably be easier to try and remember the ones I wasn’t on……not the very early ones and the later ones she did in the States, but practically all the rest.”

"A typical session in those days involved a lot of standing around waiting for the engineer to set up, and we tended to chatter between takes - a lot of which often ended up on tape when the machine was left running! It was very production-line….you didn't take months to make an LP, just a couple of weeks. It wasn't uncommon to do three songs in as many hours - not literally the vocals, but maybe the guide-vocal with the orchestra, and then you'd come back and re-do the vocals and it would all be mixed later. Whereas now, it might take months to record just one track. It's all so much more complicated now."

Was it a competitive field, I asked? Lesley and her mates were just one of several backing outfits on the scene at the time. Was there any rivalry?

"We did tend to have our own little spheres, yes - in the sense that certain arrangers would use us, others the Breakaways, and so on. But there was no rivalry, it was all very friendly. We were all interchangeable. Sometimes a girl from one set might ring us and say, 'Can you get yourself and two others for this session? Or we might ring one of them. So we occasionally intermingled, but it was always friendly."

And did it pay reasonably well? Was it possible to earn a decent crust doing just session work?

"Oh yeah. Probably one of the reasons I was a bit lazy as a writer was that I was making a reasonably good living doing sessions and backing vocals."

The talk then turned to screen appearances. And not just TV, for Lesley also had a small part in the 1963 pop movie ‘What A Crazy World’.

"Yes, well that was just typical of the madness of the time. I'd only been in the business three minutes - it literally was only a few weeks - and my manager said, 'Look, they're auditioning down at Regent Sound in Denmark Street for a film….go and sing' and I said, 'Don't be silly'. But I went ... I was so daft in those days! You don't have any nerves when you're young, you don't know enough. I wouldn't dare do it now, but I didn't give a monkey’s then, and I just went and sang and got a bit part. It was brilliant. I got £15 a day, which was a fortune in those days. I played Susan Maughan's girlfriend Lil! Allan Klein was in it too, and Joe Brown and Grazina Frame ... it was good fun."

How about TV and live work?

"I did 'Ready Steady Go!' and later, 'Ready Steady Live!'. And I also did four weeks of cabaret……which I thought was the most cruddy way you could possibly live. Turning up in say, Manchester, just you and a four-piece band. For a woman, it was very lonely, because you didn't start work 'til eleven at night and you couldn't very well go and sit in the bar of a pub all day. So after four weeks of that, I said, 'This is just mad - I'm not doing this, it's horrible'. And I refused to do any more of it. I thought it was dreadful."

One can imagine managers not being accustomed to such challenging behaviour from their young female protegees in those early days, going against the grain of the expected norms of behaviour for girl singers that permeated the whole of the entertainment business back then.

"They expected you to be very little-girlish. I remember turning up at Anglia TV studios once to promote one of my early singles, wearing jeans cut off at the knee and a man's shirt. And they said, 'What are you wearing to do the song?' And I said, 'This!' And they absolutely refused to allow me to wear it. They made me go down to wardrobe and dressed me in a shirtwaister!”

“You had to be glamorous and pretty and I just couldn't play that role, I found it absolutely impossible. You'd be the token pretty girl and I just couldn't be that. I didn't even try; I'd have just felt a total phoney. But I've been at odds with the business all along, starting very early. I always felt uncomfortable with lots of aspects of showbusiness. I think they found people like me a little hard to handle, 'cos I was rebelling already - whereas I think they were very sure of what to do with the more compliant ones, like the Susan Maughans, who were happy to play the game, to play the glamorous dolly-bird, do the TV shows and the cabaret.”

“And also, because there weren't that many girl singer/songwriters around at the time, there was nowhere to put me comfortably. Lots of girl artists, but not many who were writers too and so it was a bit uncomfortable for me because I had no-one helping me out, as it were. It has come a long way, but I think I was one of the forerunners….I was one of the early ones blazing a trail, if you like."

At this point, we began to meander through a few names of other 60s girl singers that Lesley might have encountered. As often happened during our chat, talk turned once more to Ms. Springfield, for whom Lesley still holds strong admiration.

"I thought Dusty was magnificent. I don't think this country ever fully recognised her talent - I know she had hits, but that's not the same thing. I think she was very under-valued and I enjoyed working with her enormously. I never really got to know her as a person, she's very reserved and shy - but she was great to work with, because her choice of material was so good. When we did sessions, or concerts, like at the Talk Of The Town, every song was a joy to sing. But In the end, she went off to America….but you see, she was strong-minded too - she knew what she wanted and people didn't know how to deal with that. They wanted her to fit into a tidy little mould that they'd already set for her, but she was independent and her own very strong ideas on what she wanted to do. She was reputed to have a bad temper, but that was just pure frustration with people."

"Who else at that time……Madeline I liked very much, of course….and Pat (P.P.) Arnold too. And Beverley Martyn, who I was quite good pals with. I loved her singing and she taught me my folk-picking. What little bit I know, Beverley taught me. I thought she was incredibly talented and I thought it was a terrible shame she got married and for whatever reasons, stopped being very active. Yes, Beverley was really good - put that strongly, in quotes!!”

“The Breakaways I only encountered occasionally back then, although Vicki Brown and I are really good pals now, she comes out to Oxfordshire and works with us often in our studio here. Apart from Vicki, I keep in touch with Madeline, who's godmother to one of my sons; although I have lost touch with some of the others who were around then, like Kay Garner and Sue & Sunny."

Back to records, though and following the stint at Mercury, Lesley had a brief spell at RCA, where two singles were issued. First was ‘Lullaby’, backed with ‘I Love You, I Love You’, in 1968. Both were typically lilting Duncan ballads.

The second single was a dramatically-produced and striking version of Carole King's ‘A Road To Nowhere’, coupled with the prototype version of one of Lesley's most famous compositions, ‘Love Song’, which was, as she puts it:

"A little song I'd knocked up as a suitable b-side, which in fact turned out to be incredibly lucky for me, 'cos there's been over 160 recorded versions of it.”

“Actually you know, on that original RCA recording of it, you can hear a hoover going on it! The cleaning lady came into the studio while we were doing it, and said (in Mrs Mopp voice), 'You're going to have to get out of this studio now, it's time to clean up' and she started hoovering!!”

And indeed a quick play of the single reveals the presence of said hoover, along with what sounds like a mop and bucket too! Unfortunately this embellishment was omitted, both from Lesley's own later re-recorded version for CBS and from Elton John's. Talking of whom…..

"Elton and I used to work together on sessions, especially when they wanted a group of men and women singing together. I didn't know it, but he'd collected quite a few of my records and he said he really liked my writing, and that he wanted to do one of my songs himself. So I suggested ‘Love Song’. We both once performed it together at a Festival Hall concert in front of Princess Margaret."

It was at this time that Lesley, now with CBS, was at her most visible. A collection of songs she'd been gradually accumulating in the 60s had evolved into her ‘Sing Children Sing’ album (on which Elton played) and she appeared on 'Top Of The Pops' singing the title track, which was released as a single. Both that album, and her next one, ‘Earth Mother’, released in the early 70s, won high critical acclaim - but were they big sellers?

"Kiss of death, being highly critically acclaimed! No, they got lots of radio play, which always confuses people - they think, oh, that must have been a hit, because they heard it all the time. I suppose they sold reasonably well, but not greatly so, no."

And there wasn't a hit single either, though in truth, the material was more suited to the album format anyway.

"Yes, it wasn't very instant, it took a couple of listens; it was very much a singer/songwriter climate at the time."

How does Lesley react to the suggestion that has been made that she may have been more successful had she done more live concerts?

"I think it's probably fair comment….it's hard to know, but I certainly wasn't very willing to do very much, put it that way. Firstly, because I'd had children by then and wasn't willing to leave them and secondly, because it terrified the life out of me. I hated it. I'd throw up before I went on; I was just a basket-case. I didn't look it on stage but that's because I'd had to drink a quadruple brandy to get up there."

I express some surprise at this, because my memories of Lesley singing live are of a composed, relaxed performer.

"That's because I was pissed! Don’t put that!… Heavily sedated!! No, I really was chronically nervous - the lip would twitch, the eye would twitch, and the knees would shake. I just hated it, it made me ill. So I just wasn't prepared to do much."

So was there ever a point when she felt like chucking it all in through lack of chart action, or wasn't hit status all that important to her?

"No, no, that didn't bother me - I mean, I'd always felt incredibly lucky to be able to earn a living at it, because a lot of people don't. And I still kind of make a living from it through royalties and things. I've never really analysed it, but I don't think I recognised at the time that I deliberately was not chasing stardom, because had I become famous, I wouldn't have been able to handle it anyway. I know that sounds like a failed artist saying that, but it's the way I've always felt. I think it would be hell and I've always felt that I would not be able to cope with it. And also, I started to develop an increasingly lower profile because I saw people I knew very well changing so much when they made it big, and I did not think that was for me. So I dropped out and went to live in Cornwall in '76."

That was in the middle of a period where she'd signed to the GM label and had two further LPs (‘Everything Changes’ and ‘Moonbathing’) and more singles. There then followed a break in her output until '79, by which time she'd parted from her first husband Jimmy Horowitz and married Tony Cox. She re-emerged in style with the moving re-recording of ‘Sing Children Sing’ for CBS, cut with the specific intention of raising funds for Oxfam. Tony produced, and helping out with backing vocals was an impressive line-up, comprising Madeline Bell, Kate & Paddy Bush, Vicki & Joe Brown, Billy Nicholls and Phil Lynott, not forgetting the children of Tywardreath Primary School. Lesley explains how it came about:

"An old friend of mine who had always been involved Oxfam went on to become the fundraiser for the International Year Of The Child appeal. He visited us in Cornwall and said it would be great if I could put out ‘Sing Children Sing’ again. I said it would be a nice idea, but I'd have to re-do it - I've got a history of recording things ten times! I said I'll happily re-do it and you can put it out for Year Of The Child. It did very well too; it made them more than £10,000, which is more than I've ever made from a record! It got to about No.76 in the charts - my finest shot at it so far!"

There was another lapse into silence following the charity record, which has been broken only once since then, with a rather intriguing outing for Korova in 1982, a blistering version of Dylan's "Masters Of War". Lesley:

"Even though I don't think I'm much of a singer, I occasionally get the urge to sing other people's songs and for years and years, I'd really wanted to do ‘Masters Of War’. Nobody seemed to really like the idea except me, and then I mentioned it to Tony and showed him this chord progression I'd worked out for it - as opposed to the original, where I think Dylan plays the one chord throughout - and Tony really liked the idea. So we did it as madly, and as noisily, and as aggressively as we could, because I think it's an angry song. And Korova liked it, and they put it out."

Unfortunately only days later, the Falklands War flared up, and records advocating peace caused acute discomfort in certain quarters.

"Suddenly everybody was desperately trying not to say that we shouldn't be fighting. I think it got about one radio play….it was desperate."

Destined to become a cult record though, I offer by way of consolation.

"You think so? It's daft enough!!” she laughs.

And so Lesley uprooted once more and went to live in Oxfordshire, which brings us bang up to date and begs the question - what is she doing now?

"I've been fairly quiet musically for various reasons. One is that I can't seem to think straight with two teenage sons around me! Sam's 17 and Joe's 14 and it's getting harder rather than easier because they're more omnipresent, and I can hardly put them to bed at 7pm anymore! I work on various projects that Tony has and I do bits of singing here and there. I've built up a little stockpile of tracks again, though. It's a bit like a repeat of the 60s, where I've had a lull, and I'm gradually compiling a little dossier again. I've got about three or four recorded now."

Do I detect an album in the pipeline?

"I'm thinking about it…..I'm beginning to recover energy and thinking maybe I'd like to do that. But it's hard, because as I've told you, I don't really care much for the business and I don't want to go out and sing, so I suppose it's unfair to expect a record company to invest a lot of money letting you make an album if you're not prepared to go out and promote it - which I'm not, that life is just not for me."

It occurs to me she has too many scruples for the music business and I wonder how many record companies behave with equal integrity towards their artists.

"Maybe I could sort of go on to some little low-budget label and put something out. That would suit me fine. There have been a couple of people interested, so I'm just chewing things over. But I have no great ambitions. I never have had. It seems silly to be ambitious - I don't see the point. I like to take life as it comes. I do lots of other things as well, anyway. I work at Oxfam HQ two days a week, helping to run the Resources Centre and I do two days a week working with the mentally handicapped. Plus, I've got two teenage boys, plus two dogs, plus all the other things going on. It's a very hectic life!"

Ian Chapman

August 1987